The Wisdom of not Knowing

I was raised to believe that knowledge was primary.

I was raised to believe that knowledge was primary.

If I could understand something well enough—an emotion, a relationship, a problem—then it could be solved. And if it could be solved, it could be fixed. And if it could be fixed, then things would be okay.

Knowledge wasn’t just information.

It was safety.

It was responsibility.

It was love.

Somewhere early on, knowing became the way I learned to be useful in the world. If I could explain, clarify, anticipate, or repair what was broken, I belonged. If I couldn’t, something essential had failed.

That orientation served me in many ways. It cultivated curiosity, competence, and a deep respect for learning. It also quietly taught me that not knowing was dangerous—that uncertainty meant vulnerability, and vulnerability meant risk.

So I worked hard to know more.

And yet, the longer I lived, the more obvious something became: no matter how much I knew, it was only a vanishingly small fraction of what there is to know. The world is not just complex; it is inexhaustible. Human beings are not puzzles waiting to be solved. Life does not reveal itself fully to effort, intelligence, or intention.

There is no amount of knowledge that makes life finally manageable.

Coming to terms with that was not an intellectual shift. It was an emotional one.

At first, “I don’t know” felt like a failure—an abdication of responsibility. If I wasn’t trying to understand everything, wasn’t I letting people down? Wasn’t I being careless, passive, or disengaged?

But slowly, something else emerged.

When I allowed myself not to know, I also released the unspoken belief that it was my job to fix everything: other people’s pain, unpredictable outcomes, the messy unfolding of life itself. I didn’t have to solve every problem, control every variable, or be responsible for everyone’s well-being.

Not knowing became a form of honesty.

It acknowledged a reality I had long resisted: that much of life cannot be engineered, no matter how thoughtful or prepared we are. People grow at their own pace. Loss arrives without permission. Meaning reveals itself unevenly. Some questions don’t have answers—not because we haven’t found them yet, but because they don’t exist in the form we want.

Letting go of the demand to know did something unexpected. It softened me. Without the constant pressure to figure things out, I became more present with what was actually happening. I listened more and fixed less. I tolerated ambiguity without rushing to close it. I could sit with discomfort instead of trying to metabolize it into insight or action.

This is where radical acceptance quietly enters.

Acceptance is often misunderstood as resignation, as giving up or settling for less. In reality, it is a clear-eyed encounter with what is, rather than what we hope, expect, or demand it to be. Acceptance does not mean liking reality. It means acknowledging it without distortion.

And paradoxically, acceptance becomes possible only when we stop believing we should already know how things will turn out.

When “I don’t know” is allowed, control loosens its grip. Responsibility becomes more proportionate. Compassion—for self and others—widens. Life is no longer something to be managed, but something to be met.

I still value knowledge deeply. Curiosity remains one of the great animating forces of my life. But knowledge no longer carries the weight of proving my worth or securing love. It doesn’t have to justify my existence.

There is a quieter wisdom in recognizing the limits of understanding.

Not knowing invites humility.

It makes room for mystery.

It restores relationship—with ourselves, with others, with life as it unfolds rather than as we wish it would.

And perhaps most importantly, it frees us from the exhausting belief that if we could just know enough, we could finally make life behave.

We can’t.

And in that letting go, something gentler and truer becomes possible.

With curiosity and respect for what unfolds,

Please share your thoughts on this topic in the comment section below.

Find out more about the services we have available to help you find the success you want and deserve!

© Vega Behavioral Consulting, Ltd., All Rights Reserved

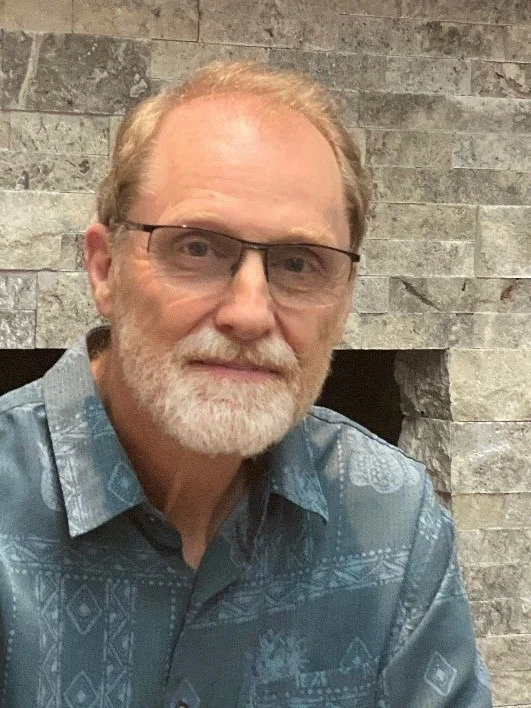

About Dr. Gary M. Jordan, Ph.D.

Gary Jordan, Ph.D., has over 35 years of experience in clinical psychology, behavioral assessment, individual development, and coaching. He earned his doctorate in Clinical Psychology from the California School of Professional Psychology – Berkeley. He is co-creator of Perceptual Style Theory, a revolutionary psychological assessment system that teaches people how to unleash their deepest potentials for success. He’s a partner at Vega Behavioral Consulting, Ltd., a consulting firm that specializes in helping people discover their true skills and talents.

Additional information about Dr. Jordan